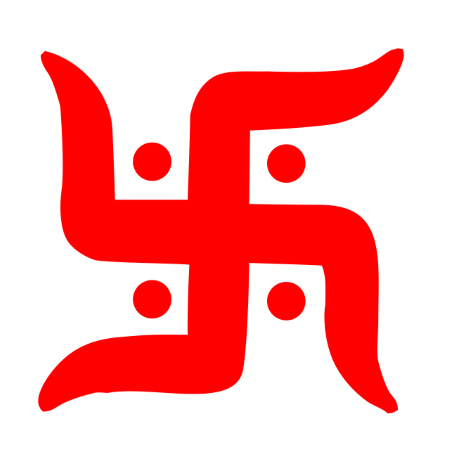

Swastika

The swastika is a symbol consisting of four crossed gamma letters.

The swastika is also called “gammadion” because, being a four-armed cross (tetrakelion), it can be formed by joining four gamma letters.

Origin of the swastika symbol

The swastika is a symbolic symbol that is widespread throughout the Eurasian area, North Africa and all of America.

The oldest swastikas appear in the ceramic cultures of Mesopotamia.

The oldest swastika found was on a piece of pottery from Susa (present-day Iran), from around 3500-3000 BC.

Also noteworthy for their beauty are those found in Samarra, in present-day Iraq.

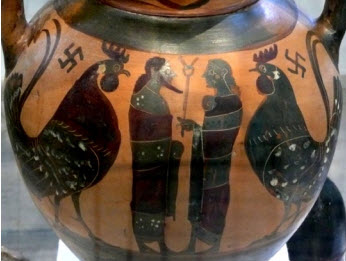

It has also been documented since the third millennium BC among the Hittites and other Anatolian peoples, the Cretans and, especially, the Greeks.

In Troy, we find the swastica in many ceramic pieces.

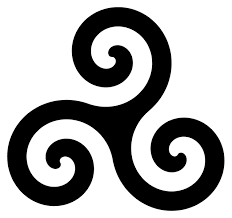

The swastika was incorporated into other Western cultures and evolved into symbols such as the Celtic trisquel:

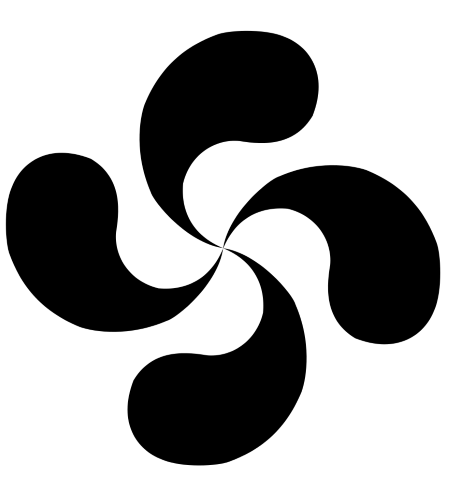

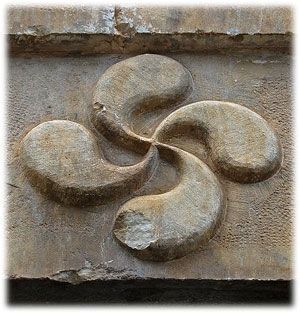

Or the vasque lauburu:

The swastika in the ancient cultures of America

In America, it has been widely used by certain North American Indian tribes, for example, the Hopis and the Navajos.

It meant good luck.

Origin and original meaning of the term “swástica”

The word swastika comes from Sanskrit, the classical language of India, and its origin derives from the Sanskrit words Swa (good) and Astik (fortune). The word swasti appears frequently in the Vedas (sacred scriptures of Hinduism) in the above meaning of good luck, success and prosperity.

The swastika in Asia and in Buddhism

In India and Nepal, the swastika is a very popular symbol and is used in various religious ceremonies. In parts of Asia where Buddhism is a religion followed by a significant part of the population, the swastika is popularly a symbol of auspiciousness and is considered to be the footprints of Buddha; and at a deeper level, in Buddhism it represents the eternal cycle of the migration of souls.

In the traditional dances of India, the hands adopt a series of positions called mudras; in some of these mudras the arms and hands are placed in a cross, reminiscent of the swastika.

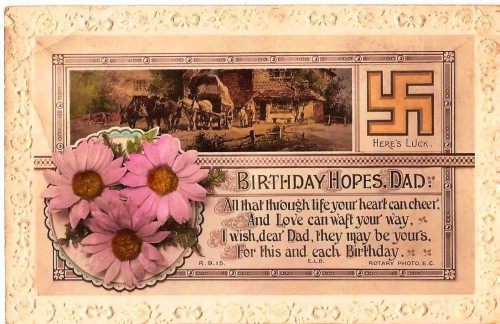

In that sense, at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, the swastika was consolidated in Western culture as a symbol of good luck, similar to a four-leaf clover or a horseshoe.

Interpretation of the swastika as a solar force

Another interpretation of the swastika is that according to which it corresponds to the movement and the solar force, being the scheme of the solar wheel with rays in the four directions.

The great archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann discovered a large number of swastikas during his excavations of ancient Troy, which reminded him of similar ones found on the banks of the Oder River in Germany, from which he believed he discovered a link between the ancient Germans, the Greeks Homeric and Vedic India, uniting Eastern and Western religious traditions under one Aryan symbol. This led to the swastika being considered an Aryan symbol.

This interpretation was largely supported and popularized by the Danish professor Ludvig Müller, who in 1877 described it as the emblem of the “Aryan supreme god”, and considered it to be the symbol of the supreme god in the Iron Age.

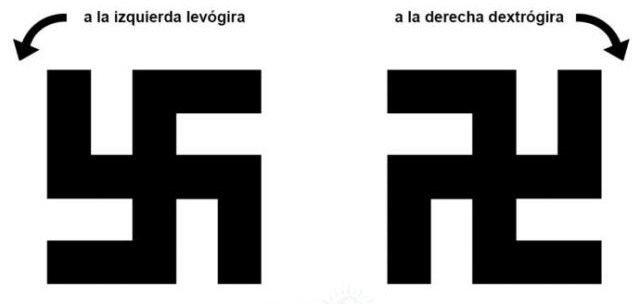

types of swastika

There are two variants of the swastika, the right-handed (turning to the right) and the left-handed (turning to the left). The right-handed swastika is associated with birth, and the left-handed swastika is associated with death. Together they represent the cycle of life .

The swastika in nationalist Germany in the early 20th century

During the 19th century in Europe, the ideas that associated the swastika with the Aryan and its relationship with the sun crossed the academic field and entered the field of esotericism, and hence its misinterpretation according to the interests of certain groups.

In The Secret Doctrine (1888), Helena Blavatsky associated the swastika with the hammer of Tor, the Germanic god of thunder. A few years earlier, Blavatsky had incorporated a right-handed swastika into the seal of the Theosophical Society.

Later, in 1891, Ernst Ludwig Krause disassociated the swastika from occultism to link it to writings related to German nationalism.

Finally, in the book On the swastika, 1921, Jörg Lechler places the origin of the swastika in central and northern Europe, despite the fact that the existence of older Mesopotamian swastikas was already known at that time. From there, the Tule Society went on to adopt the swastika as a symbol by Nazism. Note that of the two swastikas, this Society chose the left-handed swastika, which is associated with death.