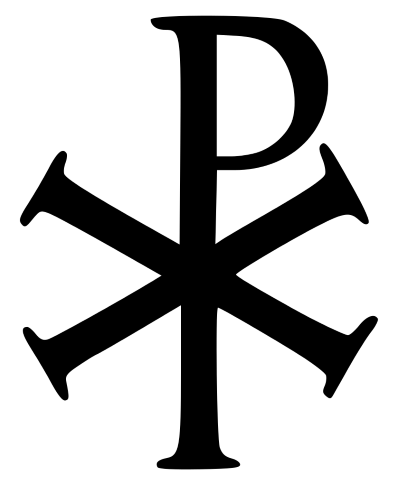

Chi rho

It is formed by superimposing the letters, chi (X) and rho (P)

The Chi Rho is one of the first cruciform symbols used by Christians. It is formed by superimposing the first two letters of the word “Christ” in Greek, chi = ch and rho = r.

Source

Chi rho as an abbreviation for the name of Christ

The first two letters of the name of Christ in Greek ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ are Chi and Rho, for this reason the Chi-Rho, also known as chrismon, is used as an abbreviation of the name of Christ.

This type of representation of the name of Christ is known as a Christogram, which is to form an abbreviation of the name of Christ using a combination of letters.

The chi rho in pre-Christian times

In pre-Christian times, the Chi-Rho symbol was also meant to mark a particularly valuable or relevant passage in the margin of a page, abbreviating chrēston (“useful, productive”).

A variant of the term would be Xrestus (“useful”), which was a common name for a slave in the Greco-Roman world.

Adoption of chi rho by the roman empire

The Chi-Rho symbol was adopted by the Roman Emperor Constantine I (r. 306–337 AD) as part of his military banner.

According to the Latin historian Lactantius, the Emperor Constantine the Great dreamed that he was commanded to “make the heavenly sign delineate on the shields of his soldiers” on the shield of his soldiers, asking him to substitute it for the imperial eagles on the insignia of the soldiers After this dream, Constantine adopted the Latin motto “In hoc signo vinces” (“With this sign you will win”).

Lactantius describes the symbol as “the letter X, with a perpendicular line drawn through it.”

Constantine did as the dream commanded him, and fought that day against the forces of Maxentius, who disputed his power, whom he defeated at the Battle of Milvian Bridge (312 AD).

This is how Lactantius describes it in his work De mortibus persecutorum:

And now a civil war broke out between Constantine and Maxentius. Although Maxentius remained within Rome, because the soothsayers had predicted that, if he left there, he would perish, and, nevertheless, he would direct the military operations through the generals capable of him. In forces he exceeded his adversary; for he had not only his father’s army, which had deserted Severus, but also his own, which he had lately led out of Mauritania and Italy. They fought, and Maxentius’ troops prevailed. Finally Constantine, with unwavering courage and a mind prepared for every event, led all his forces into the neighborhood of Rome, and encamped opposite the Milvian bridge. The anniversary of the reign of Maxentius, that is, the sixth, was approaching, and the fifth year of his reign was coming to an end.

Constantine was directed in a dream to cause the heavenly sign to be outlined on the shields of his soldiers, and thus proceed to battle. He did as he was commanded, and marked on his shields the letter X, with a perpendicular line drawn through it, and it turned thus at the top, being the cipher of Christ. Having this XP sign (☧), his troops stood up in arms. The enemies advanced, but without their emperor, and crossed the bridge. The armies met and fought with the greatest efforts of valor, and firmly held their ground. Meanwhile, a sedition broke out in Rome, and Maxentius was vilified as someone who had abandoned all concern for the security of the common good; and suddenly, while he was showing the circus games on the anniversary of his reign, the people shouted with one voice: “Constantine cannot be beaten!” Dismayed at this, Maxentius stormed out of the assembly, and having summoned some senators, he ordered the sibylline books to be searched. In them it was found that:

“On the same day, the enemy of the Romans should perish.”

Led by this response to the hopes of victory, he went to the field. The bridge at its rear was broken. Seeing that, the battle became more intense. The hand of the Lord prevailed, and the forces of Maxentius were defeated. He fled towards the broken bridge; but with the crowd pressing on him, he was driven headlong into the Tiber.

Lactancio. De mortibus persecutorum:

After Constantine, the Chi-Rho became part of the official imperial ensign.

Late Roman-era helmets stamped with the Chi-Rho have been discovered, as well as coins minted during the reign of Emperor Constantine also with the Chi-Rho.

Similar symbols

Some authors note the resemblance of the Chi Rho with the Egyptian Ansata cross or Ankh.

Also its resemblance to the Staurogram and the IX monogram.

The chi rho as a chrismon in Romanesque buildings

We can find the chi rho along the Romanesque routes in Spain and France in its form of Crismón

The Chrismón “is represented in its oldest form as the superposition of the first two Greek signs: “Equis – Rho” and the addition on the sides of the first of the apocalyptic letters “alpha and omega”, the first and last of the Greek alphabet symbolizing that the one represented by the anagram, is the beginning and the end of all things.”